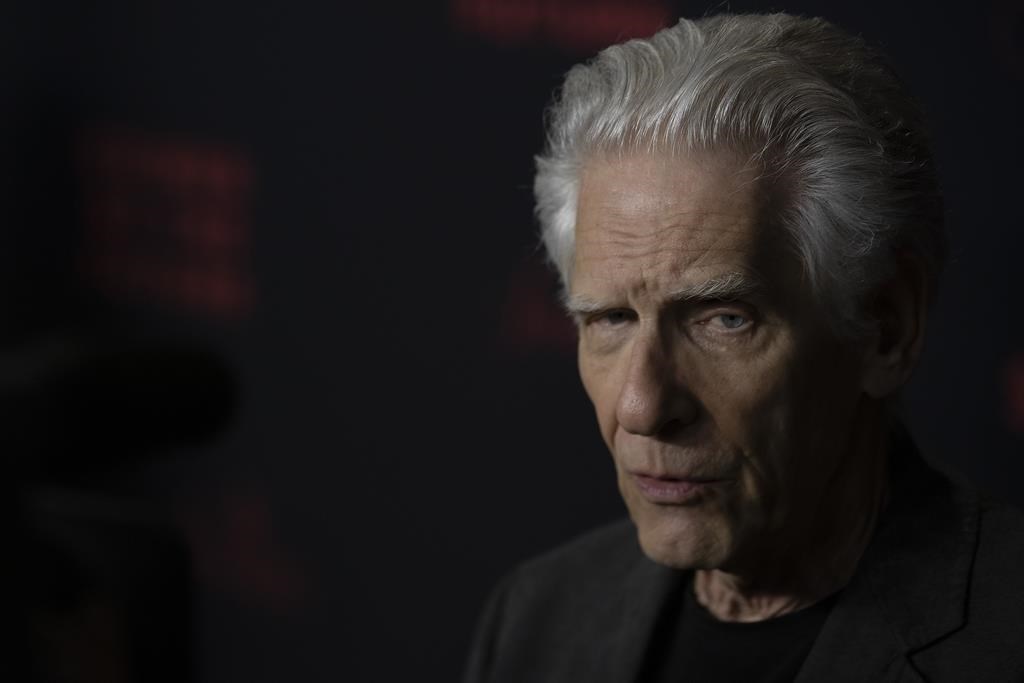

TORONTO — If you ask David Cronenberg or his longtime muse Viggo Mortensen, the Toronto director has always been fascinated by dissection — not just the bodily kind, but the emotional.

Call it “a desire to be open,” to borrow a line from his latest film, “Crimes of the Future.”

“He is gentle and kind, but can be ruthlessly cutting,” Mortensen said in an interview Monday ahead of the film’s Toronto premiere, adding with a smirk: “In his sense of humour! Underneath it all, there’s a playfulness.”

That may come as a surprise to some, as Cronenberg’s latest has already earned a dark reputation, after a series of walkouts at an early screening last week at Cannes Film Festival.

A throwback to the filmmaker’s earlier body horror, including 1975’s “Shivers” and 1983’s “Videodrome,” the film is set in a time when the human body has evolved to the point of experiencing entirely new mutations and no pain. Microplastics are also food.

It’s a world Mortensen’s Saul Tenser fully embraces. So much so that he and his partner Caprice (Léa Seydoux) take to crudely cutting him open and examining his insides as performance art.

Despite the carnage, Cronenberg agrees that there’s always been a sentimentality at the core of his work.

“I mean, this is a movie in which there are no villains, and everybody is wishing the best for everybody else, but trying to find out what that is,” he says.

“There is a kindness in it that maybe wouldn’t have been obvious unless you read the script … but that’s how it flowed for me when I was writing it.”

He wrote the film back in 1998, with not a single word of dialogue altered in the decades since. And yet it feels incredibly topical — microplastics, for instance, were detected in human blood for the first time earlier this year, making the seemingly preternatural “Crimes of the Future” feel all the more possible.

“So many people were shocked that the body seems to be able to handle microplastics without instantly producing cancer or whatever,” says Cronenberg.

“Does that mean that our bodies actually are predisposed to being able to use them? We don’t know yet. But as I say, the film is not as satirical or as absurd a proposal as one might think.”

Another prescient theme is the way in which the characters’ bodies are always up for public consumption, flicking at the dangers of technology and government encroaching on bodily rights. The ultimate question, the film seems to propose, is who has ownership over the skin we live in?

“As an artist, you’re always pushing against repression,” says Cronenberg.

“It’s automatic, because anything that you do in art, no matter how frivolous or superficial, there’s still somebody who’s going to want to suppress it.

“So I don’t really give it a lot of thought while I’m creating, because I just know it’s going to be there. Early in my career, it was very obvious.”

He’s referring to when the Ontario Censor Board would cut parts of his films, including 1979’s “The Brood,” without consulting him.

“That’s as Stalinist as you can get. It was always censorship, and you’re always aware of that. But if you’re going to be an artist, that’s part of the deal.”

Mortensen adds that it’s a “fear of new ways of looking at the world,” but fortunately when an artist like Cronenberg is told something can’t or shouldn’t be done, it serves as a “stimulus” for rebellion.

And he should know — this is the pair’s fourth film together, following “A History of Violence,” “Eastern Promises” and “A Dangerous Method.”

Mortensen jokes, “It’s almost unbearable at this point,” to which Cronenberg adds, “His senility has been a problem, his lack of focus, his inability to memorize his lines, but other than that, no problem.”

Seriously though, Cronenberg says, “It’s a love affair that continues to be a love affair. We’re very close friends, we know each other’s families, we have a long history of non-violence together.”

But even with a trusted A-list collaborator and a resumé that spans five decades, it took three years just to accumulate financing for “Crimes of the Future.”

Then there’s Cronenberg’s upcoming project, a film called “The Shrouds,” which shoots in Toronto next year. It began as a series for Netflix, but the streamer pulled out after reading two of Cronenberg’s early scripts.

Has he ever considered toning it down a little? Absolutely not, Cronenberg says, “I don’t even think of those terms.”

It’s that commitment to his visceral visions that has led to a genre practically all his own, one that often explores the intersection between eroticism and pain, à la 1996’s “Crash.”

In “Crimes of the Future,” in place of car crashes that titillate, this is a world in which autopsy is spectacle.

“I think everybody — whether they’re conscious of it or not — is totally fascinated by their bodies,” says Cronenberg.

“It takes a lot to create a human, and most of that in the beginning is coming to terms with you as a physical entity in the world. The thing that we photograph most as directors is the human body; that’s our subject matter.

“So, to me, it’s a primal thing that you work with as an artist. … Of course, sexuality is completely and obviously involved.

“(It’s) such a potent force, so many things in human history are driven by sexuality, even though it might seem to be politics or fashion or something, underneath there is always this sexual drive, which is one of the reasons I love Freud so much.”

It’s a clear comparison; the Austrian neurologist and founder of psychoanalysis was, in Cronenberg’s words, one of the first to posit that sexuality can be “an engine of creativity and violence.”

Similarly, the Canadian director has always cut deep. As Mortensen jokes, “he’s just stitching up a few wounds.”

This report by The Canadian Press was first published May 31, 2022.