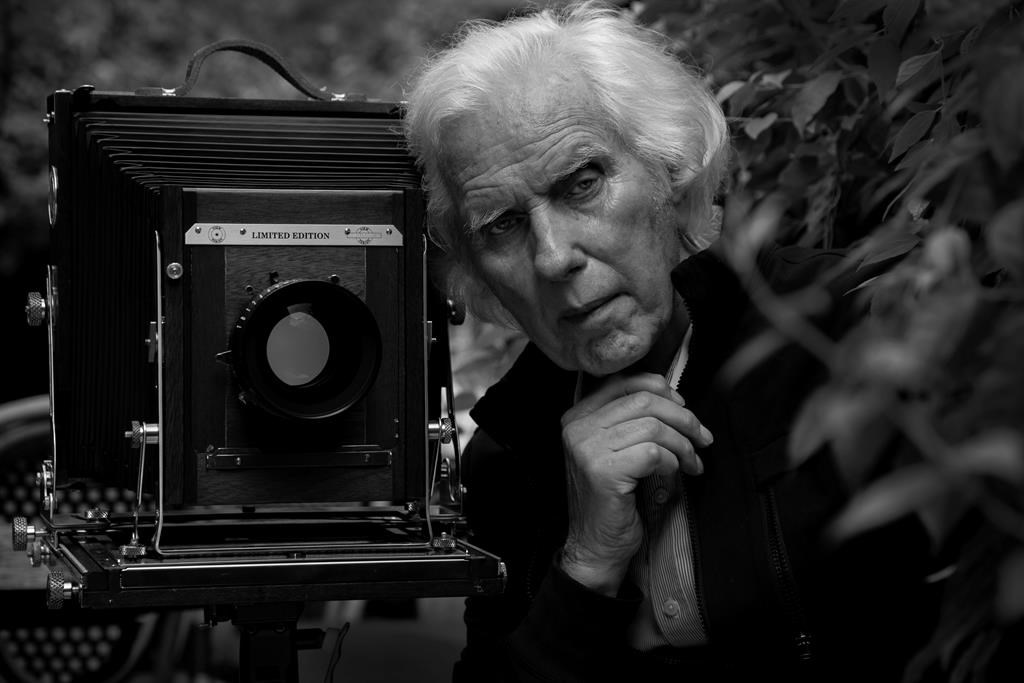

TORONTO — Canadian photographer Douglas Kirkland captured Judy Garland, Audrey Hepburn and an array of other Hollywood legends, but it was the young photographer’s intimate shots of Marilyn Monroe taken in her final year that changed everything for him.

The cameraman, who earned the trust of many celebrities, died Sunday in Los Angeles, his wife Francoise Kirkland confirmed. He was 88.

“I have a crater in my heart,” she said in a brief email to The Canadian Press.

Kirkland rose to prominence in an era when magazine photoshoots could shape a celebrity’s image.

Born in Toronto, as a young child he moved to Fort Erie, Ont., a town directly across the border from the United States. Growing up, he was inspired by the copies of Life magazine his father brought home from the clothing shop where he worked.

Kirkland took his first photograph when he was seven or eight years old on a Brownie box camera. The image was of his family standing outside their home on Christmas Day.

After attending a Buffalo high school, he enrolled in the New York Institute of Photography but ended up moving back to Canada after his parents became concerned he might be drafted in the Korean War.

He took newspaper jobs at the Fort Erie Times Review and later the Welland Tribune, which he credited with giving him the editorial experience of news photography.

Kirkland eventually made his way back to the U.S., landing a job at Look magazine, where he took portraits of actress Elizabeth Taylor in 1961 that put him on the radar as a budding staff photographer.

But it was those images of Monroe, taken the same year, that became some of her most memorable. He was only 24 years old and still learning the industry when he shot the actress seductively wrapped in white bed sheets.

More people asked about this experience than any other celebrity shoot, Kirkland told “CBS This Morning: Saturday” in a 2013 interview about his book “An Evening with Marilyn.”

He described a rainy night when he and two colleagues from the magazine visited Monroe’s home to discuss possible concepts.

“What I had in mind and hoped for, as a young photographer, was to get something really sizzling — I was almost embarrassed to say that,” he remembered.

“She said at the end, ‘I know what we need. We need a bed, a white silk sheet … Frank Sinatra records and Dom Perignon.'”

A few days later, those tools helped get Monroe into the mood for what became an unforgettable shoot that landed him on the magazine’s cover and set his career on fire.

Kirkland would go on to work at Life magazine and photograph other legends of the era, including Jack Nicholson, Coco Chanel, John Lennon and Margot Kidder’s 1976 Playboy pictorial. He also captured Mick Jagger and secured exclusive access to Michael Jackson on the set of the “Thriller” music video.

Toronto gallery owner Izzy Sulejmani described Kirkland’s optimistic and friendly personality — his “joie de vivre” — as what opened so many doors with the famous.

“Access back in the day was very difficult,” he said.

“An actress or a model will give you everything if they like you, and more time if they like you, and obviously he achieved that. You know, he spent 10 days with Coco Chanel.”

Kirkland’s trustworthiness also helped him land jobs as a photographer on film sets for what became some of Hollywood’s most timeless classics, capturing images of “The Sound of Music,” “2001: A Space Odyssey,” “Titanic” and “Moulin Rouge.”

His assignments outside of the film industry included capturing the Trans Siberian Railway to Japan and the fashion world in Bali.

Sulejmani’s Izzy Gallery hosted a retrospective of Kirkland’s work in 2016, a deal he made by calling Kirkland and his wife to propose bringing some of his images to Toronto.

“It was like he was waiting for this call for 50 years because nobody from Canada ever called him and we were the first,” he said.

“He was very happy to come back, you know, because he did shows all over the world, Australia, Europe — everywhere, but never in Canada.”

Kirkland’s work is part of permanent collections at the Smithsonian, the National Portrait Gallery in London and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Oct. 4, 2022.