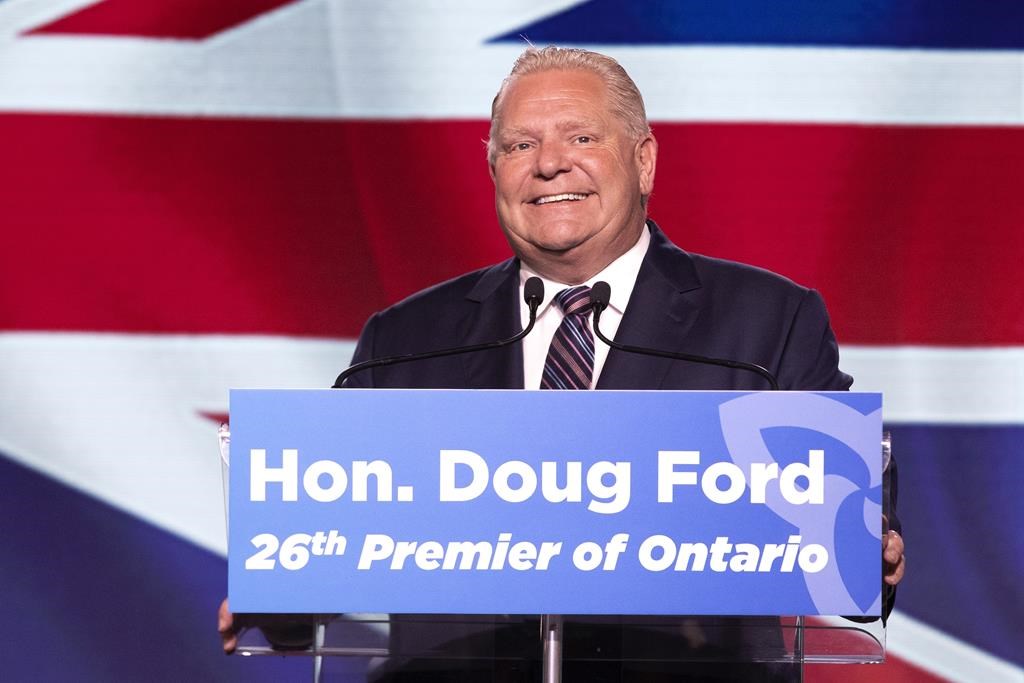

Advocacy groups are renewing calls for electoral reform in Ontario after Doug Ford’s Progressive Conservatives were re-elected with another majority last week despite historically low voter turnout and most voters casting ballots for other parties – though experts say it’s likely a non-starter.

Of the 43 per cent of eligible Ontarians who participated in the June 2 election, 40 per cent voted for the Progressive Conservatives, handing the party 83 legislative seats. Close to 53 per cent in total voted for the NDP, Liberals and Greens, but those parties will have a combined 40 seats in the legislature. The Liberals won nearly a quarter of the popular vote but will hold just eight of the 124 available seats.

The majority win means Ford’s government will essentially be able to pass any legislation it wants without having to win support from other parties, just as it did during its first majority mandate.

Electoral reform advocates have pointed to the outcome as fodder for their cause to scrap the first-past-the-post system, which some argue allows governments to wield power that’s disproportionate to the amount of support they’ve actually won from the public.

Under the first-past-the-post system, voters pick one candidate in their riding and the person with the most votes wins. The successful candidate doesn’t need to win a majority of votes to take the riding.

Many would like to see a proportional representation system instead, under which the percentage of seats a party holds in the legislature would reflect the popular vote.

“The Ontario election results were a gross misrepresentation of what voters said with their ballots,” read a Twitter post from Fair Vote Canada, an organization that supports moving to a proportional system. “Majority governments should have the consent of a majority of voters.”

Non-profit advocacy group Democracy Watch has also proposed a new voting system to better reflect the popular vote, along with mandating voter education ads from Elections Ontario, and messaging informing people of their right to decline a ballot.

The group also called the historic low voter turnout a “clear crisis” that should “raise alarm bells” about the legitimacy of the provincial government.

“More and more voters know from their experience of the past few decades of elections that they are not going to get what they vote for, and are likely to get dishonest, secretive, unethical, unrepresentative and wasteful government no matter who they vote for, and as a result no one should be surprised to see voter turnout at such a low level,” Democracy Watch co-founder Duff Conacher said in a written statement.

Cameron Anderson, a political science professor at Western University, said people are understandably frustrated with the outcome, though he noted that the results could have been murkier if, for example, the party with the most votes didn’t win enough seats to form government.

“It was a fairly decisive victory among those who cast ballots, but the aftermath is what it is, and it’s unpalatable to many, for sure,” he said in an interview.

Amid calls for change, Anderson noted that supporters of the current system can make the case that majority governments offer stability without disruption or fear of snap elections.

He also pointed to referendums on electoral reform that have been held in Canadian provinces – including in Ontario in 2007 – that ended up sticking with the status quo.

Back then, Ontarians voted against a proposal to implement a mixed member proportional voting system. That model – which the NDP had campaigned on this time around – tries to lend some of the stability of the first-past-the-post system to a fully proportional government, by having some legislators elected in local districts and others for the whole province from party lists.

“Changing the system is not easy and is no panacea,” Anderson said, adding that finding compromise or agreement on a new system is challenging when balancing the interests of citizens and political parties.

Three of the four major political parties had promised to change the province’s electoral system, but it’s unlikely that another attempt at reform will come any time soon. Ford, maintaining that his party received a clear mandate from voters with 83 seats, ruled out the possibility when asked about it the day after the election.

“I think this system has worked for over 100 and some odd years. It’s going to continue to work that way,” he said.

The Liberals had proposed a ranked ballot system, under which voters mark their first, second and subsequent choices. If no candidate wins more than 50 per cent of the vote, the contender with the fewest votes is dropped from the ballot and their supporters’ second choices are counted. That continues until one candidate emerges with a majority.

The Greens, meanwhile, campaigned on a fully proportional system. After re-electing just one representative despite winning more than five per cent of the vote, the party highlighted that proposal in a Twitter post that said it would keep advocating for that change “so that the legislature better reflects how people vote.”

The federal Liberal government also promised – and failed to deliver on – electoral reform.

Justin Trudeau ran on the pledge in 2015, saying that the federal election held that year would be the last to use the first-past-the-post method, a pledge he would ultimately renege on.

Emmanuelle Richez, an associate professor of political science at the University of Windsor, said sitting governments and elected representatives generally lack the political will to introduce difficult voting system reforms that could threaten their power.

She also highlighted a “lack of popular appetite for electoral reform,” despite the current discussion in Ontario, pointing to the past referendums across the country.

“It’s a niche topic that’s just not a priority for most Ontarians,” she said of the concept. “My prediction is that you’ll never see it in Canada.”

This report by The Canadian Press was first published June 7, 2022.